Example Analyses of the Wood Chips and Paperboard Manufacturing Industries as Biomass Markets.

Introduction

The production of biofuels is a primary intended use for biomass. Because the cellulosic biofuels industry is still developing, there is not yet sufficient capacity in biofuel refineries to utilize biomass crops grown for cellulosic biofuels. However, the bioeconomy overall is growing, and many products other than biofuels can be manufactured from biomass. These byproducts may be alternate markets [i] for growers of biomass crops until the biofuels industry reaches capacity. However, biomass growers may not be aware of these alternate markets or whether the markets are viable for specific biomass raw materials.

This fact sheet provides a market analysis approach that can be used to analyze any of these potential markets for the sale of biomass raw materials. Two examples were selected for application of the market analysis: the wood chip industry and the paperboard industry

Contents

- Porter’s Five Forces Market Analysis

- Analysis Example: The U.S. Wood Chips Industry

- Example: The U.S. Paperboard Manufacturing Industry

- Closing Comments

- End Notes

- Contributors to This Article

Porter’s Five Forces Market Analysis

Market analysis is integral to understanding customers as well as the forces that shape competition in the markets. It is fundamental to developing competitive priorities and marketing strategies—generally expressed in terms of cost, quality, delivery (speed and reliability), and flexibility (features, variety, and mix)—that would successfully enable a company to break into new markets or increase its share in its existing markets [2].

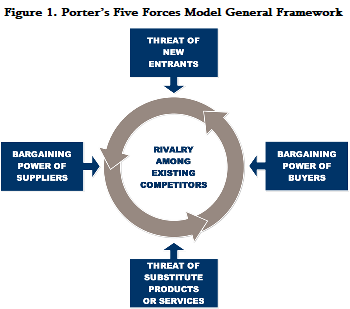

Porter’s Five Forces Model is a comprehensive yet easy-to-use market analysis tool that helps companies gain understanding of their industry’s customers. It is based on five forces that shape industry competition, shown in Figure 1 and briefly described accordingly.[3]

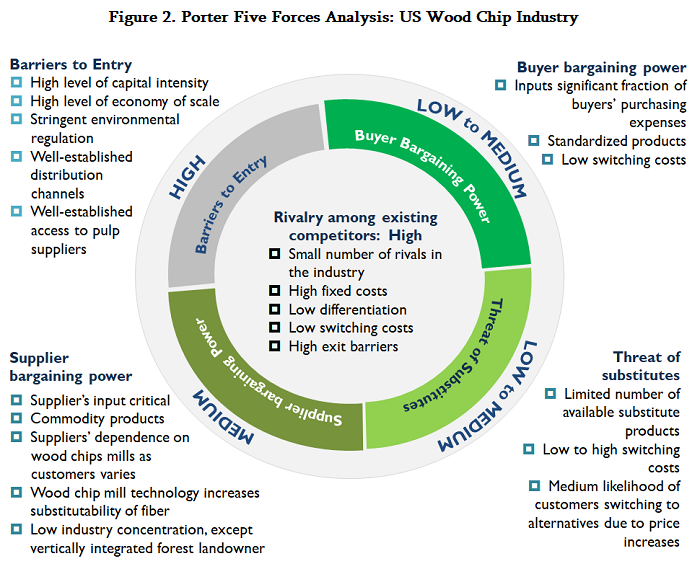

The configuration of the five forces differs by industry. In this fact sheet, the U.S. wood chip and paperboard manufacturing industries are used as illustrative examples for the Porter Five Forces analysis, highlighting opportunities and challenges for biomass growers competing in the supply market of these industries. Because biomass is the input material supplying these two industries, supplier bargaining power is the most relevant force for biomass producers in the Porter model.

- Rivalry among existing competitors: The current intensity of industry competition, as determined by the number of existing competitors and what each player is capable of doing. Rivalry is high when companies in the industry are numerous or are roughly equal in size and power (thus equally selling a product or service), when the industry is growing, and when customers can easily switch to a competitor’s offering.

- Bargaining power of suppliers: How much power and control suppliers have over the potential to raise prices of the products and service provided. Sources of supplier power include the number of available suppliers, switching costs from one supplier to another, the presence of available substitutes, and how critical the inputs are to the industry.

- Bargaining power of customers: The power of customers to affect pricing and quality. Customers have power when there are large numbers of sellers and when it is easy to switch between different sellers. In contrast, customers have low power when they purchase products in small quantities and the seller’s product is very different from any of its competitors’ products.

- Threat of new entrants: Barriers to entry into the marketplace in the industry. These can include patents, economies of scale, capital requirements, and government policies.

- Threat of substitute products or services: The availability of products or services that can serve the same purpose. This is measured by the amount of available substitute products or services, the level of switching costs, and the likelihood of customers switching to alternatives in response to price increases. This differs from bargaining power of customers in that the emphasis is switching to different products rather than to different suppliers.

For biomass growers, the model is especially useful from three key persepectives.

- Customer characteristics and needs. The model enables understanding of the characteristics of customers at the industry level in terms of their major competitors and customers, basis of competition, products, and services provided, and the scope of the industry’s market. These insights are vital to identifying: Who are the customers? What do they need? How do they make their buying decisions? How easily can they find substitute products?

- Buyer-supplier balance of power. The model enables understanding of the ‘balance of power’ between biomass growers as suppliers and the customers as buyers.

- Competitor characteristics and competitive positions. The model enables understanding of biomass growers’ competitors operating within the supply market of the industry, notably pertaining to: Who are they? What are products and services they provide? What are their competitive positions?

Porter Five Force Analysis Example: The U.S. Wood Chips Industry

Wood-chip processing facilities are primarily engaged in turning wood fiber into wood chips. Activities involved in wood-chip processing operations typically include:

- Obtaining, receiving, and storing wood-fiber raw materials (defined in the next paragraph)

- Maintaining and managing storage facilities

- Screening wood-fiber raw materials for chipping

- Debarking, chipping, drying, and storing wood chips

- Reclaiming and loading wood chips onto transport vehicles for customer delivery

Quality

Wood-fiber raw materials for wood-chip processing facilities come from four primary sources:

- Forest residues (e.g. timber harvest residues such as branches and treetops)

- Forest thinning, such as young or small-diameter trees, and material from forest clearing, such as low-lying bushes and vegetation

- Saw mill residues (e.g. slabs, edges, sawdust)

- Urban wood wastes (e.g. municipal solid waste, construction, and demolition waste), and purpose-grown woody biomass (e.g. short-rotation woody crops like willow).

Each of these raw material sources differs in quality based on such characteristics as ash content, moisture content, energy content, uniformity, and contamination (e.g. rocks, dirt, debris). As a result, a wood-chip facility processor’s choice of wood-fiber raw materials depends on the specifications for its end products.

Quality affects the suitability of these wood-chip end products for different applications in a suite of markets that includes landscape mulches, fuel for wood-fired boilers, pulp and paper, fiberboard, wood pellets, and biofuels, to name a few. A classification guideline for wood-chip end products is provided by the Biomass Energy Resource Center (BERC) [5] :

- Grade A. Paper-grade chip (high quality)

- Grade B. Bole chip (medium quality)

- Grade C. Whole-tree chips (low quality)

- Grade D. Urban-derived wood fuel (lowest quality)

Other Factors

Other factors influencing selection of raw material sources and suppliers may include price, availability, and services. A key cost factor is the transportation distance from wood source to customer facility. Once selected, wood-chip facilities generally procure wood fibers from the suppliers under long-term contracts. Market forces for the U.S. wood chip industry are summarized in Figure 2. Some of the factors depend on scale.

Porter Five Force Analysis Example: The U.S. Paperboard Manufacturing Industry

Paperboard mills are primarily engaged in turning fibrous materials into paperboard stocks. These intermediate products come in a wide variety of styles and qualities suitable for different usage requirements. However, more than two-thirds of all paperboard produced by U.S. paperboard mills is converted into cardboard boxes, containers, and packaging, with a much smaller proportion delegated to other products.[6] This major product line was expected to grow from $169.1 billion to $186 billion by 2017, according to the latest report issued by Smithers Pira, The Future of Packaging in North America to 2017.[7]

Paperboard is made from fibrous materials that come mainly from two sources— virgin sources (mainly wood pulp), and recovered fibers (also known as secondary fiber, recovered paper and board, and recycled paper products), notably old corrugated containers.[8] Non-wood fiber is currently used to a smaller extent.[9] Five influential factors in choosing the types of fibers used for paperboard production are:

- Supply availability

- Total costs of procurement (including purchased prices and logistics costs)

- Contribution to product performance requirements

- Compatibility with existing manufacturing infrastructure

- Contribution to success of products in the marketplace.[10]

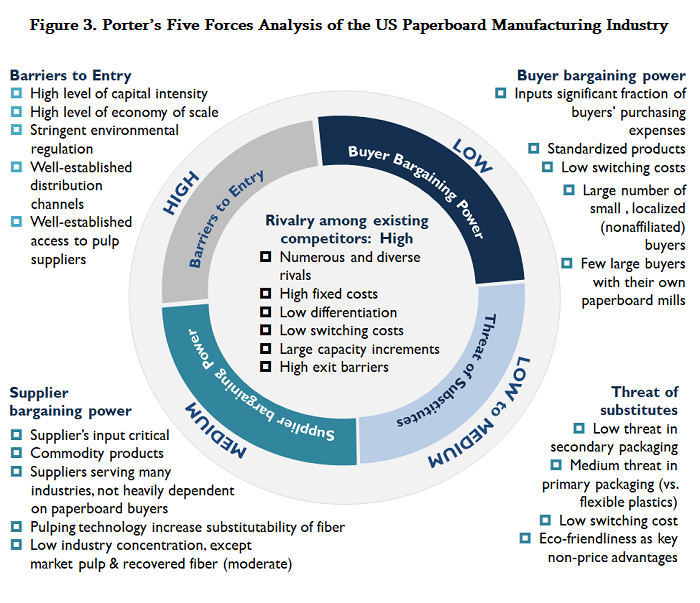

Figure 3 exhibits the configuration of the five forces in the paperboard industry. From the biomass growers’ perspective, a number of insights into customers’ characteristics and needs are noted. According to the FAO annual survey of world pulp and paper capacities, only about 16 percent of the wood pulp produced in the United States was sold on the market as pulp during 2012–2014,[11] suggesting that the majority of pulp produced for paper and paperboard is made by integrated mills for their own operations. The growth prospects for the major product line discussed earlier and the practice of in-house pulp production render the paperboard-manufacturing market favorable as an opportunity for biomass growers to supply fiber raw material.

Closing Comments

Based on the example of the U.S. paperboard-manufacturing industry, several characteristics of this industry make it promising for biomass producers as suppliers. The supplier input is critical, yet the industry has the technology to extract wood pulp from a variety of sources, allowing the biomass industry to emerge as a natural alternative for paperboard manufacturing. Nevertheless, the industry has operated using other sources in the past and is likely to continue to do so until the biomass cost becomes competitive with traditional sources and can provide the raw material reliably.

As for the U.S. wood-chip industry example, the industry appears to be a promising customer market for biomass producers as suppliers. The supplier input is critical and the industry continues to expand, pushing the demand for raw materials, which, in turn, increases the prices of raw materials provided by traditional suppliers. In the future, biomass producers may be able to position their material as a competitive alternative to these traditional suppliers, provided the yields are high and the cost becomes competitive with the traditional sources.

Two industries were analyzed in this fact sheet, but this framework can be applied to any industry market. Its use can provide biomass growers a useful guide for the feasibility of entering markets through understanding buyers’ characteristics and needs, the balance of buyers vs. grower powers, and the competitiveness of growers against other suppliers. Information necessary for the analysis can be based on the biomass growers’ knowledge of the specific markets, industry reports, or government publications.

|

An overview of all biomass markets can be found in the NEWBio whitepaper publication entitled, Market Opportunities for Lignocelluosic Biomass: Multi-tier Market Identification Framework. This white paper provides data for industry and companies collated from various sources, including Penn State business library databases (e.g. IBISWorld, Hoover’s, and Standard & Poor’s NetAdvantage), academic and industrial business journal databases (e.g. ABI/INFORM Complete, Academic Search Complete [Ebsco]), industry association publications, and government publications, as well as company websites, blogs, and annual reports. |

End Notes

This Fact Sheet is a NEWBio Project Resource, which provide information on the research, opportunities and challenges in developing a sustainable system for the thermochemical production of biofuels from perennial grasses grown on land marginal for row crop production.

[1] Thomchick, Evelyn, and Kusumal Ruamsook. 2014. “Market Opportunities for Lignocellulosic Biomass: Multi-tier Market Identification Framework.” NEWBio White Paper.

[2] Chi, Ting, Peter P. D. Kilduff, and Vidyaranya B. Gargeya. 2009. “Alignment between Business Environment Characteristics, Competitive Priorities, Supply Chain Structures, and Firm Business Performance.” International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 58 (7): 645–69. Sarmiento, R., G. Knowles, and M. Byrne. 2008. “Strategic Consensus on Manufacturing Competitive Priorities: A New Methodology and Proposals for Research.” Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management 19 (7): 830–43.

[3] Porter, Michael E. 2008. “The Five Competitive Forces That Shape Strategy.” Harvard Business Review, January.

[4] Myers, Mason. 2013. “Five Forces by Michael Porter — Fundamentals Through Graphics.” Blog posted on February 3.

[5] BERC – Biomass Energy Resource Center. 2011. “Woodchip Heating Fuel Specifications in the Northeastern United States.” The Biomass Energy Resource Center.

[6] Hoopes, Stephen. 2014a. “Paperboard Mills in the US.” IBISWorld Industry Report 32213, June.

[7] Western Container. 2013. “Paperboard and Corrugated Packaging Top Market Trends in 2013.” Blog.

[8] EPA – US Environmental Protection Agency. 2012. “Paper Making and Recycling.” US Environmental Protection Agency, November 14. Hoopes, Stephen. 2014a. “Paperboard Mills in the US.” IBISWorld Industry Report 32213, June.

[9] Bajpai, Pratima. 2012. “Chapter 2: Brief Description of the Pulp and Paper Making Process.” In Biotechnology for Pulp and Paper Processing, Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 7–14. Hoover’s. 2014. “Pulp & Paper Mills.” First Research Industry Report. Iggesund Paperboard. 2014. “The Paperboard Process.” Product Information, 2014-08-26. Singh, Pooja, Othman Sulaiman, Rokiah Hashim, Leh Cheu Peng, and Rajeev Pratap Singh. 2013. “Using Biomass Residues from Oil Palm Industry as a Raw Material for Pulp and Paper Industry: Potential Benefits and Threat to the Environment.” Environment, Development and Sustainability 15 (2): 367–383.

[10] National Council for Air and Stream Improvement. 2013. “Effects of Nonwood Fiber Use.” http://www.paperenvironment.org/PDF/nonwood/NWF_Full_Text.pdf

[11] FAO – Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2013. The 2013 FAO Survey of World Pulp and Paper Capacities, 2012–2017. FAO – Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2014. The 2014 FAO Survey of World Pulp and Paper Capacities, 2013–2018.

[12] Thomchick, Evelyn, and Kusumal Ruamsook. 2015. “Market Opportunities for Lignocellulosic Biomass: Analysis of the Paperboard Industry.” NEWBio White Paper.

Contributors to This Article

Authors

- Kusumal Ruamsook, research associate, Center for Supply Chain Research, Smeal College of Business, Penn State University

- Evelyn Thomchick, associate professor of Supply Chain Management, Department of Supply Chain & Information Systems, Smeal College of Business, Penn State University

Peer Reviewers

- Sarah Wurzbacher, Extension Educator, NEWBio Consortium, Penn State University

- Michael Jacobson, Professor of Forest Resources, Penn State University

The Northeast Woody/Warm-season Biomass Consortium – NEWBio is supported by Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant no. 2012-68005-19703 from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Led by Penn State University, NEWBio includes partners from Cornell University, SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, West Virginia University, Delaware State University, Ohio State University, Rutgers University, falseUSDA’s Eastern Regional Research Center, and DOE’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Idaho National Laboratory.